The Role of Government Messaging in the Covid-19 Battle - Seton Hall University

Tuesday, April 28, 2020

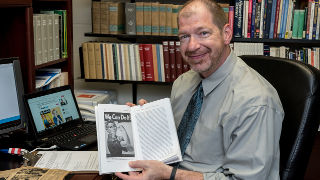

Perhaps best known for his work uncovering "the real Rosie the Riveter," which was featured in media around the world (including the front page of The New York Times and People magazine), he specializes in the rhetoric and messaging of WWII.

With the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic, comparisons to the WWII home front abound in media as the world, and the United States in particular, attempts to come to grips with a deadly foe. Public messaging in that effort has received mixed reviews. Professor Kimble, who recently published a feature piece in The Washington Post entitled "The real lesson of World War II for mobilizing against covid-19" weighed in here to further clarify why that messaging is important and how it can be more effective.

Messaging is important any time there is a group effort. We know from studying even

small work teams that they function much more effectively when everyone is working

in concert and not at cross purposes. Clear messaging among the group members makes

that possible.

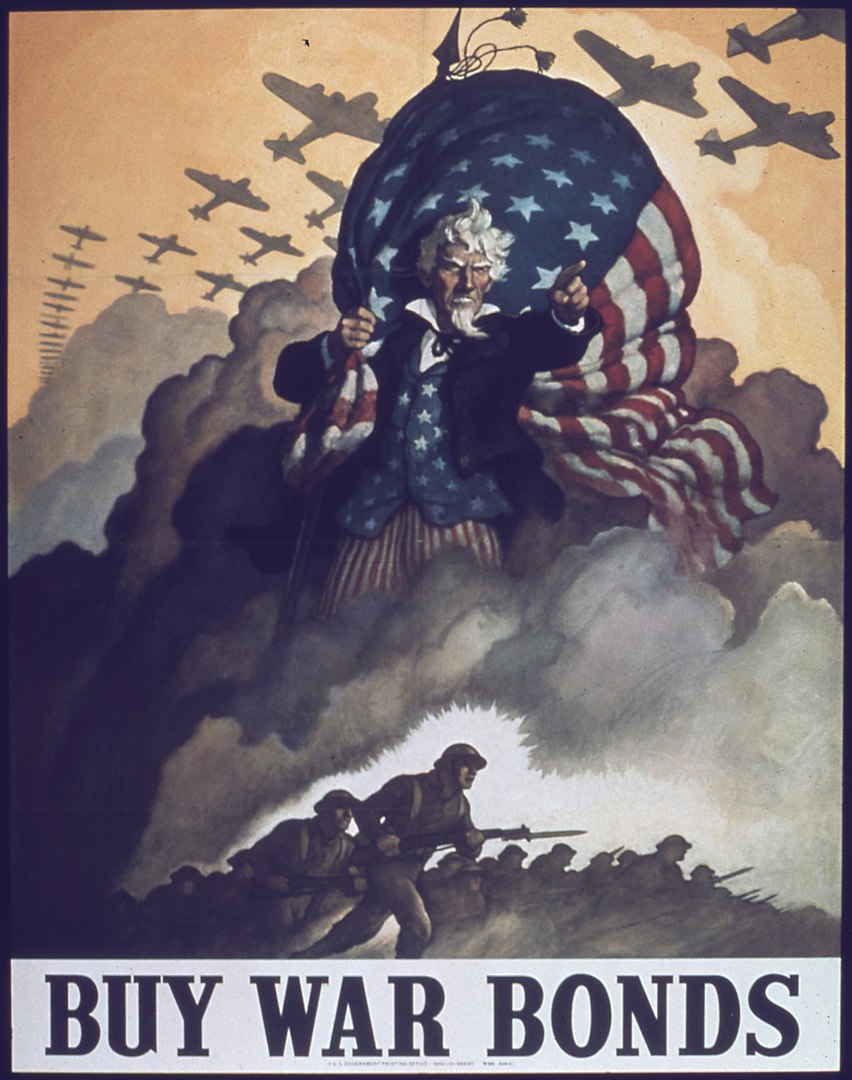

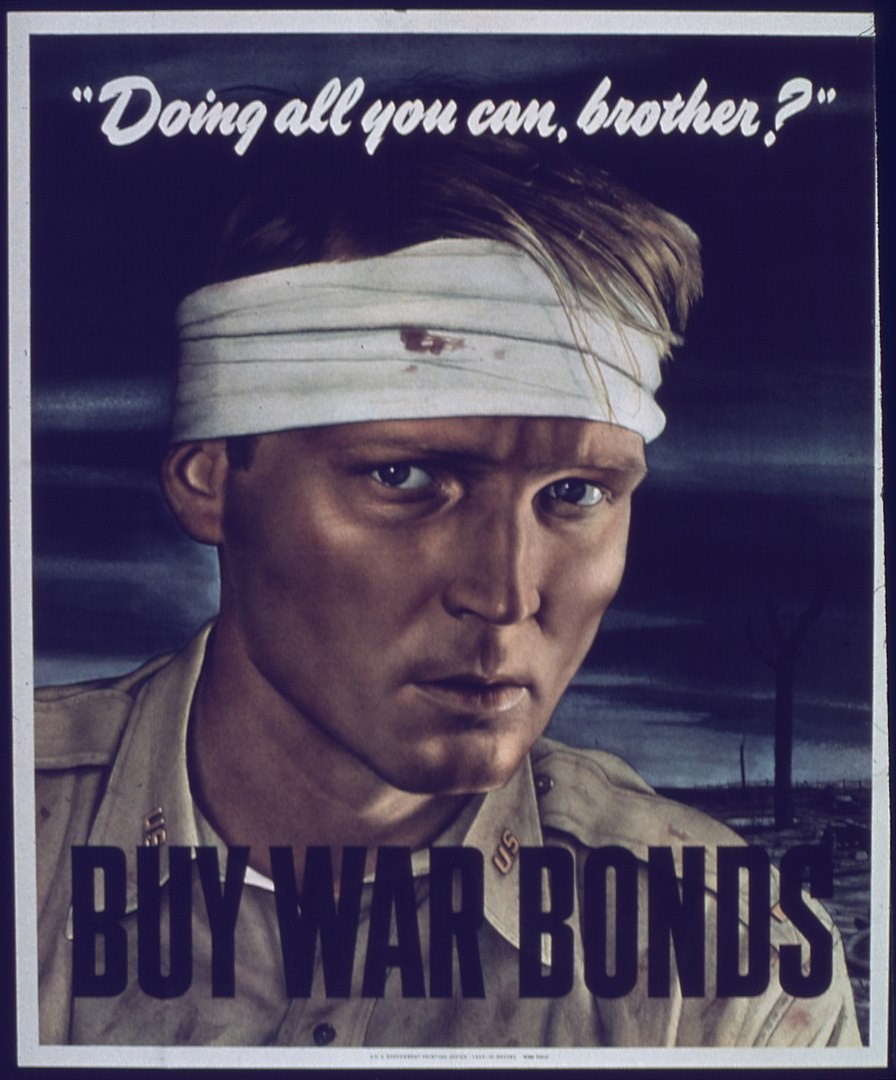

Now when you're looking at an effort that encompasses an entire state, or an entire country, the messaging is even more important because all of the various contributors are decentralized and dispersed. Consider the U.S. home front during World War II (an effort that has come up repeatedly in recent weeks as an analogy for the current crisis). There you had some 130 million citizens whose participation in the war effort was crucial. Whether it was buying war bonds to finance the effort, gathering scrap metal to be melted down for munitions, taking double shifts in arms factories even if you had no related experience, or just writing scores of letters to front line troops to boost morale, the role of the home front was deemed essential to victory.

But how do you get all of those people working in concert? The most obvious answer is that you don't, at least not completely. The larger the group, the more outliers there are. On the home front, there were people who continued to protest U.S. participation in the war (even after the Pearl Harbor attack), newspapers that printed secret war plans, citizens who circumvented rationing through black markets, and those who spread rumors or were careless with information that could be overheard by enemy spies.

Your goal, then, is to get most people on board. Messaging from the government or another central source is critical to getting the message out clearly and consistently so that everyone in the target population is aware of what is necessary, and a critical mass of adherents can be formed.

2. But isn't this just propaganda?

There's no way around it: yes, these messages are propaganda by almost any definition.

Much has been written over the years about the dangers of government propaganda. We

are right to be wary. There is no better example than Nazi Germany, or perhaps the

Stalinist era of the USSR, to show how dangerous and overwhelming government propaganda

can become.

Yet it would be too easy to paint all forms of propaganda with the same broad brush. To my mind, there is a significant difference between a message from the Nazi hierarchy dehumanizing perceived enemies of the state and a message from a White House pandemic authority asking citizens in a given area to quarantine themselves. It would be great if we could never find ourselves in a situation in which a government propaganda message is necessary. But in the context of a bona fide national emergency — such as a war effort, or a pandemic crisis — there are times when domestic propaganda is both essential and urgent. We are in the midst of such a time, in my opinion.

One of the most critical aspects of any propaganda message is its source. Organizations

and individuals who seek to mislead through propaganda often do not identify themselves

as the source of a message (or, even worse, they might try to convince recipients

that the message actually comes from a legitimate source). Such messages reflect awareness

on the part of propagandists that when you know the source of a message, you can properly

assess its credibility.

When those who create messages for dissemination to the masses have motives that are above board, they should have no fear in identifying their organization as the source. In fact, all government or institutional propaganda should clearly identify itself as such. That allows you, the recipient, to take the source into consideration as you receive the message. Source transparency is a key differentiator in this context.

The variable of message source also highlights the idea that too many sources can muddy the outcome. If you go on social media now you'll find an uncharted forest of messages about Covid-19. At least some of them are either misleading, based on junk science or both. It's better to pay attention to messages from official sources, or at least those with recognizable expertise. If you're following the advice of an anonymous YouTube video, not only are you more likely to be acting on misinformation, but you also are less likely to be paying attention to better guidance from sounder sources.

4. What kinds of messages are needed?

Messages aimed at a mass audience during an emergency should be clear, as concise

as possible, consistent with other messages, and suitable for repetition or multiple

exposures over time. If a message is confusing, contradicts other messages, or receives

limited exposure, it is unlikely to have the intended effect. Here, at least, the

government's currently decentralized approach has produced more confusion than clarity.

Some of the states are doing a good job with their messaging, but the overall environment

right now is too chaotic to be as effective as it could be. It would be interesting

to study the messaging behind South Korea's largely successful fight (so far) against

the virus. There's a lot of admiration for that country's testing and tracking operations,

but I bet that behind it all there's been a well-thought out, clear, and consistent

messaging campaign.

5. What should the government avoid in its Covid-19 messages?

As noted above, messages that are unclear, contradictory, or not rolled out for a

wide audience over time (unless a specific audience is the target) will tend to be

less effective in mass messaging. While there are some effective messages out there

right now, I think that the general approach at the federal level has been far too

hazy and hands-off. It's a sort of free-for-all now, and it ultimately makes for a

poor comparison to the overall effectiveness of the US government's messaging efforts

on the home front during World War II.

James J. Kimble, Ph.D., is also the author of Mobilizing the Home Front: War Bonds and Domestic Propaganda (2006) and Prairie Forge: The Extraordinary Story of the Nebraska Scrap Metal Drive of World War II (2014), as well as the writer and co-producer of the movie documentary Scrappers: How the Heartland Won World War II. His most recent book, co-edited with Trischa Goodnow, is called The 10¢ War: Comic Books, Propaganda, and World War II (2016). He is presently Book Review Editor for the academic journal Presidential Studies Quarterly.

Categories: Arts and Culture